- Joined

- Apr 9, 2014

- Messages

- 1,337

- Reaction score

- 1,680

- Points

- 113

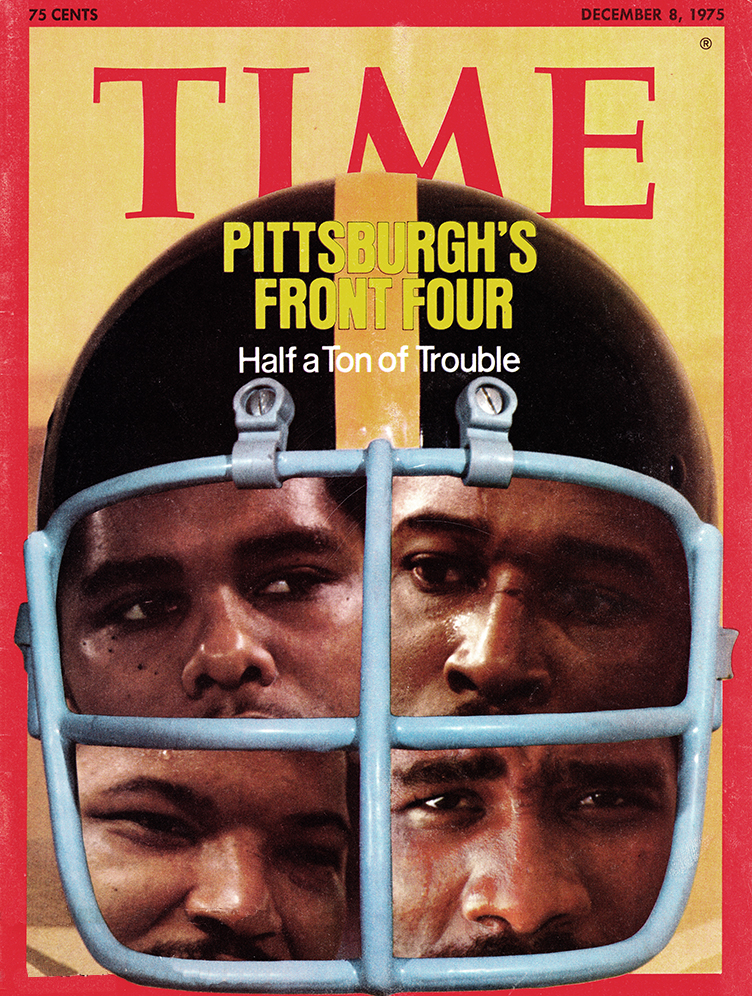

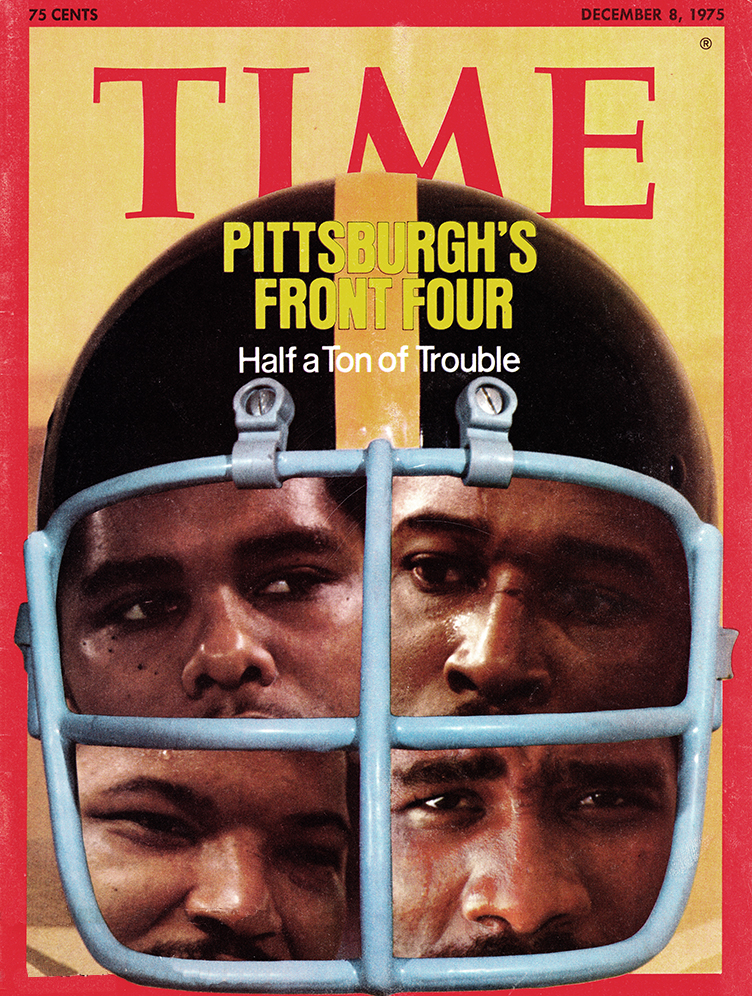

In these unsettling times of 'football divas' it is settling to reflect on a time when there were no divas.

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,947577,00.html

HALF A TON OF TROUBLE

Monday, Dec. 08, 1975

It was his 27th birthday and Ernie Holmes, defensive tackle for the Pittsburgh Steelers, was picking up the meat for his party. Not at the supermarket or butcher's, though. Holmes was personally slaughtering a calf at his father's farm outside Houston. "I gave him a forearm lift," says Holmes, describing his barnyard battle with the beast. "That knocked him into the fence Then I put a full nelson on him." Finally Holmes dropped the animal with a high-powered rifle. "Forty-five minutes later," he says, "we had the calf skinned and dried."

The National Football League is full of quarterbacks who have been shown no more mercy. Not to mention running backs and offensive linemen. Playing with a raw violence that is rare even when judged by the bare-knuckle standards of his sport, Ernie Holmes knows how to slaughter an offense.

On most teams his performance, and personality, would make Holmes famous. Not on the Steelers. With Pittsburgh, he is not even the best-known defensive lineman. There are three reasons: Fellow Tackle "Mean" Joe Greene and Ends L.C. Greenwood and Dwight White, each a prototype of menace at his position and a striking figure off the field. Greenwood, 29 is a brutal tackler, although he says he hates contact and would rather not be known as a football player. Greene, 29, after a season of tossing linemen and runners around like rag dolls, goes home to cultivate his vegetable garden. As for White, 26, it is hard to know exactly what he will do at any time. "There's no question that I'm schizoid," he says. "I might be three or four people. I know I can be evil."

These are the men who make up the meanest front four in football, a half ton of trouble for any offense. Moving like a band of marauding behemoths (average size 6 ft. 4 in., 260 lbs.), they smother runners at the line of scrimmage, flatten passers, and send offensive linemen into disarray. "There are some great lines in the league," says Washington Redskins Head Coach George Allen, architect of one himself, "but the edge has to go to Pittsburgh. They put fear in the heart of a passer."

They do more than that. Dumping quarterbacks a league-leading 40 times last season was only the beginning of the front four's contribution to the Steelers. They set the tone for the entire defense and it was the defense that carried the 42-year-old Pittsburgh franchise to its first Super Bowl championship last year. The creation of patient, low-key Head Coach Chuck Noll, who drafted all but two of the starting defensive players, and Steelers Founder and Owner Art Rooney, who gave Noll the backing he needed to build slowly over the past six years, the defense is the cornerstone of Pittsburgh's leadership in the N.F.L. When Pittsburgh defeated Minnesota 16-6 in the Super Bowl, the defense limited the Vikings to 17 yds. rushing. Minnesota Running Back Chuck Foreman spoke for the league when he pleaded with the Steeler front four: "C'mon, you mothers, give us a yard."

Before this season ends, that call may well be heard again. Going into last weekend's game against the stumbling New York Jets the Steelers were riding an eight-game winning streak and an overall won-lost record of 9-1. That was good enough to pui them in first place in the Central Division of the American Conference the toughest division in the N.F.L. Their biggest conference obstacle on the way to the Super Bowl is a likely playoff showdown with the rugged Oakland Raiders. If the Steelers survive that, they will probably face either the Vikings or the Los Angeles Rams in the Super Bowl next month in Miami.

A Super Bowl in Florida will be the natural conclusion for a sunny NFL. season. Despite, or perhaps because of, the collapse of the rival World Football League, the N.F.L. this fall registering a jump in attendance (averaging 56,000 per game) and an increase in TV ratings. And why not? Some 40% of the games are being won by 7 points or less, not to mention a rash of sudden-death thrillers.

It is ironic that four of the key protagonists of this season should be Charles Edward ("Joe") Greene, Dwight Lynn White, Ernest Lee Holmes and L.C. Henderson Greenwood. Though front fours have been well publicized in pro football, the Rams "Fearsome Foursome" and the Vikings "Purple People Eaters during the past decade, quarterbacks and running backs still remain the celebrities of the sport. Certainly the action along the line of scrimmage gets only passing attention from TV cameras and fans. But this trench warfare is as fierce as anything in sport. Grunting and cursing, players club, ram and pound each other in two- and three-second rumbles that begin anew with every play.

Until about 15 years ago, the defensive lineman's primary objective was to come out of the rumble stopping the run. No longer. Faced with increasingly sophisticated passing attacks, the interior defensive line must now think first about rushing the passer. To do that, which requires them to overcome powerful, oversize blocking linemen who launch the offensive attack, front fours operate as a team with complicated strategies of their own.

In Pittsburgh, planning starts every Tuesday morning at the Steelers' offices in Three Rivers Stadium when Joe Greene and Co., including back-up lineman Steve Furness, gather with Defensive Line Coach George Perles to go over movies of the previous Sunday's game. Screening a specially edited reel that covers only defensive play by Pittsburgh, Perles, 41, a former Michigan State tackle, shows his players their mistakes in a numbing montage of slow motion, stop-action and reverse-run images. On Wednesday, films of the next opponent come under scrutiny. The group focuses on the abilities of each offensive lineman: Has some bull-like youngster been developing deceptive moves? Has a veteran fallen into a habit pattern that tips off his plans? Perles points out the formations and plays he thinks the opposition will use. In afternoon practice sessions, the front four polish the latest pass-rushing tactics Perles has devised.

Today a team wins or loses on games within the game. A particular "game" can be a certain pass-rushing pattern. Instead of sending each lineman driving straight ahead into blockers on the shortest route toward the quarterback, a game can use one lineman to run interference for another. The basic Steelers games are called "me" and "you" (you because of the U-shaped route one of the linemen runs, me just as the opposite of you). In the me game, Left End L.C. Greenwood will push himself and his blocker inside toward the offensive guard, who would normally block Left Tackle Joe Greene. While Greenwood is keeping that area clogged and trying to bust through himself, Greene is cutting to the open area outside and sweeping back in on the quarterback. The you game is the reverse, with Greene running interference on the outside while Greenwood cuts over the offensive-guard position (see diagram).

Right End Dwight White and Right Tackle Ernie Holmes use the same tricks on their side of the line, often on the same play as Greenwood and Greene. These combinations are called "double" games. To put the offensive line further off balance, Greenwood and Greene will sometimes charge using a me while White and Holmes employ the you. In still another refinement, the two tackles can run their own separate game, crossing paths as they bull ahead. That is called a "torn" game (T for tackle and torn).

Last week, in the Pittsburgh-Houston game, the payoff for all this strategy was obvious. In the second period, with the Steelers ahead only 9-3 and the Oilers beginning to show some offensive muscle, Greenwood wheeled in over the middle of the offensive line, forcing Houston Quarterback Dan Pastorini out of the pocket. As he fled, Pastorini threw a wild pass that was intercepted, setting up what proved to be Pittsburgh's game-winning touchdown. (Final score: Steelers 32-9.) The turnover was the result of a me game George Perles had devised for certain third-down passing situations.

The front four, of course, do not neglect defense against running plays, and for these too they employ more than one tactic. Rather than lining up in the traditional formation, defensive ends opposite offensive tackles, defensive tackles against guards, and the middle linebacker responsible for the center, the Steelers use what is called a "stunt 4-3." In this alignment, Joe Greene edges toward the center. His assignment: to stop both guard and center, leaving the middle linebacker unmolested, free to deck the runner as he crosses the line of scrimmage.

The best devised strategies, of course, are only as good as the players executing them, and that is where Pittsburgh has the advantage over any other team in the league. "What impresses me," says George Allen, "is that they're all so quick. They move like linebackers." Alex Karras, Monday football broadcaster and former all-pro defensive tackle with the Detroit Lions, puts it this way: "It's simple. They're the biggest, strongest, fastest and meanest." The players speak for themselves:

White: "That offensive lineman is there to stop me from getting to the quarterback. He might as well forget it. He'll just get caught between the stink and the sweat. I'll kick, slap, gouge. On that field, I take no prisoners."

Greene: "I hate to lose. It makes me ugly. You don't want to know me after we lose a game."

Greenwood: "If I have to intimidate, I can pound on a man's head the whole game."

Holmes: "I don't mind knocking somebody out. If I hear a moan and a groan coming from a player I've hit, the adrenaline flows within me. I get more energy and play harder."

For such huge men, the front four have exceptional speed. With hands the size of bear paws and thighs the thickness of a railroad tie, Joe Greene measures 6 ft. 4 in. and weighs 275 lbs. Even so, he drives through the 40-yd. dash in less than five seconds, as fast as many running backs. Dwight White (6 ft. 4 in., 255 lbs.) and Greenwood (6 ft. 6 in., 230 lbs.) are faster, and Holmes (6 ft. 3 in., 260 lbs.) is only a minisecond slower.

These reserves of strength and speed are harnessed in physical techniques used to bull past blockers. All four start with the head butt, driving their helmets into the heads of the opposite offensive linemen like bull moose battling for their lives. Once the offensive lineman has been hit, each man has a specialty. Greenwood likes to use the "slip" move, pushing past his blocker. White prefers to knock his opponent aside with an "uppercut" shove under the shoulder. Holmes is a master of the "club," using one of his blacksmith forearms to belt a blocker to the side, and the "push and pull," in which he pushes a guard off balance and then pulls him aside. Greene is an expert at all four techniques. "When Joe stomps you, it's not infuriating," says Steeler Center Ray Mansfield, who faces him in practice. "It's more like frightening. Did you ever see a dog get hold of a snake?"

The front four are so aggressive, in fact, that it sometimes works to their disadvantage. Offensive plays that capitalize on a hard defensive rush have gained yardage against the Steelers this year. Screen passes, for example, are designed to lure pass rushers toward the quarterback, who then dumps the ball to a runner waiting a few yards downfield.

Of the front four, Ernie Holmes is the most volatile, living and playing precariously close to the edge of rage. "I don't know what my life is," he says, "except there is something pounding in back of my head."

Nearly three years ago, his marriage broke up, depriving Holmes of two adored sons. Driving through eastern Ohio after leaving them, he started firing a pistol at trucks. Before he was stopped, Holmes shot at a police helicopter and wounded a cop during a chase through woods. "Three trucks tried to drive me off the road," he says. "It was all I needed to snap."

He pleaded guilty to assault with a deadly weapon. After the Steelers promised to provide help for him, he was placed on five years' probation. Holmes spent two months in a psychiatric hospital. "I was considered stone crazy until the Super Bowl last year," he says. "Now I'm back on the bases."

Last season, in what he describes as a "mystic haze," Holmes shaved his head, leaving only an arrow-shaped pattern of hair facing forward, hence the nickname "Arrowhead Holmes." These days, for relaxation, Holmes tends a collection of exotic fish, including a piranha that feeds on a goldfish a day. "It's the destructive time of year," Holmes notes. He himself will consume a light meal of 15 spareribs and nine chicken parts, his lifelong nickname is "Fats", and occasionally polish off heroic amounts of Courvoisier cognac in an evening. His hard times appear to be over. Earning a comfortable living like his three colleagues (exactly how much, they won't say), Holmes finds tranquillity in shooting pool, or playing chess on a board that reflects his expansive nature: it is three feet square.

He was born in Jamestown, Texas. Indeed, all of the front four, except White, whose father was college-educated, come from poor rural backgrounds in the South. They all played their college football for obscure schools. For Holmes, it was Texas Southern University in Houston, where campus buildings "had bullet holes the size of silver dollars" from student riots.

The product of a far more peaceful campus, East Texas State, Dwight White, with his missing front tooth and boyish grin, makes a deceptively mild first impression. He laughs easily in a high-pitched voice and is the teaser and clown of the front four, letting out jungle cries in practice, needling Joe Greene about the publicity he gets, and booming to reporters, "I am the epitome of masculinity." But just beneath the engaging extravert there is a hair-trigger temper and barely repressed violence. "There are circumstances," he says, "when I can get so angry and pissed-off that I'll do damage if I don't cool down fast."

White, a bachelor, now rents an apartment in the fashionable Squirrel Hill section of Pittsburgh, after rooming briefly with Joe Greene. The separation reflects the general state of the relationship between the four defenders: cordial but not intimate. "I couldn't live with Joe," White explains. "He'd put on music late at night."

Dwight does play chess with Greene and also Holmes. He is the most active of the four in the world beyond the Steelers. In the offseason, he works for a Commerce Department program that finds jobs for black college students from Pittsburgh's Hill district.

If White is usually the liveliest of the front four, L.C. Greenwood can be the quietest. "Most of the time I like to be by myself," he says. "I'm a loner. I want to lay back and live." That philosophy is reflected in almost everything unmarried L.C does, from collecting American Indian jewelry and playing cards to shunning contact during practice. "1 try to preserve myself for the game," he says. "That's when I come to play."

Of the four, Greenwood struggles hardest to escape his image as a jock. "I can do without the inhuman looks people give me," he says. "Even kids do it. When I tried to do some teaching in the offseason, the kids said, 'Hey, man, you're a football player, not a teacher. We don't want you here.' I'm just an object."

Greenwood began taking football seriously as a high-school freshman in Canton, Miss. Hoping to get a degree in pharmacy at college, Greenwood attended Arkansas A M & N on a football scholarship. By the time he was graduated in 1969, L.C. had abandoned his hopes of owning a drugstore; he reported to the Steelers' training camp as their tenth-round choice. "I couldn't believe it when I made the team," he says.

That same year, another lineman made the cut: Joe Greene. Arriving overweight after a contract holdout, the Steelers' first-round draft choice looked like a pushover to some Steeler veterans. As soon as he started blowing by blockers, they knew better. They also learned that off the field Joe is a sensitive, gentle friend, still trying to overcome natural timidity and live down the image that he is a bully. (He got his nickname, which he does not like, while playing football at North Texas State University, where the team was called the "Mean Greens.") "I come off as being ugly," he complains. "Sometimes I get the feeling I am that way. I don't like what all that makes me become."

So far his image has not made much of a dent on his character. At home in Duncanville, Texas, in the offseason, Greene lives in a sprawling ranch house. He enjoys just sitting around watching his three children, Charles, 7, Edward, 6, and Joquel, 2. "I've missed a lot of their growing up," he says. Other times, Greene is happy weeding the cucumbers and squash in his garden, sipping a glass of white wine while he listens to the Temptations, or helping his wife Agnes clean house. A compulsive tidier, Joe says, "It gives me peace of mind to know things are in their place."

One thing that does not give Greene peace of mind is the predominantly white cast of his neighborhood. "I'm not a pacesetter," he says. "If I'd known earlier how this neighborhood was composed, I probably would have chosen somewhere else." Dwight White felt the same way recently when he bought a home outside Dallas. Such unease among black athletes is nonexistent on the field. For one reason, blacks equal or outnumber whites on some teams and account for about a third of the N.F.L.'s 1,100 players. For another, equality of position is accepted, quarterback, the last major barrier, has fallen with the Los Angeles Rams black starter James Harris. "It's a competitive game," says White, "and color isn't a factor."

It certainly hasn't stopped Joe Greene from becoming the Steelers' leader. "Joe's first year," says Steeler Linebacker Andy Russell, "I didn't see how all the emotionalism could be real. He's the only guy I know, he can be playing a great game himself, but if the team's losing he gets into a terrible depression." Art Rooney senses the same fire. "That Joe Greene," he says. "I've never seen a player lift a team like he does."

When Joe lifts, there is more than enough talent to respond. Behind the front four on defense are three of the most mobile linebackers in the league: eleven-year Veteran Russell on the right side, lanky Jack Lambert in the middle, and hard-hitting Jack Ham on the left. Behind them are four defensive backs with the speed and experience to spoil most passing patterns.

On the offense, Quarterback Terry Bradshaw, 27, has been slow developing, but since late last season he has directed the Steeler attack like a young Johnny Unitas. This year he has completed better than 60% of his passes, scrambled for first downs, and given his powerful backfield plenty of opportunities to carry the ball. When Franco Harris is at fullback, that may be all a team needs to win. The son of an Italian mother and a black father, Harris is a runner of the Jim Brown model: strong, shifty and astonishingly difficult to bring down. Last year he was the Most Valuable Player in the Super Bowl, breaking the rushing record for the game as he rumbled for 158 yds. This season Harris trails only O.J. Simpson in rushing stats.

Bradshaw has other weapons as well. Second-year Wide Receiver Lynn Swann has become one of the best pass catchers in the N.F.L., moving through his patterns with the speed of a college sprinter and the fakes of a ten-year veteran. Running Back Rocky Bleier, who was wounded by shrapnel while serving with the Army in Viet Nam, last year became a bruising blocking back for Harris, as well as a dangerous runner in his own right. Helping it all come together in offense is an experienced, hard-charging line that can move out almost any front four, except their own.

If the offense falters, the Steelers can always turn to the front four to hold off the opposition for a while, and perhaps even to score. Joe Greene dreams about just that possibility. "I visualize techniques," he says. "Some of them are just ungodly. Run over a guy, hurdle, jump six feet, put three or four moves on him so he freezes. No flaws. Perfect push and pull on the guard, jump over the center. Another blocker, slap him aside. Block the ball when the quarterback throws it, catch it, and run 99 yards." If that's the defense,

Pittsburgh shouldn't have to wait another 42 years to win a second championship.

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,947577,00.html

HALF A TON OF TROUBLE

Monday, Dec. 08, 1975

It was his 27th birthday and Ernie Holmes, defensive tackle for the Pittsburgh Steelers, was picking up the meat for his party. Not at the supermarket or butcher's, though. Holmes was personally slaughtering a calf at his father's farm outside Houston. "I gave him a forearm lift," says Holmes, describing his barnyard battle with the beast. "That knocked him into the fence Then I put a full nelson on him." Finally Holmes dropped the animal with a high-powered rifle. "Forty-five minutes later," he says, "we had the calf skinned and dried."

The National Football League is full of quarterbacks who have been shown no more mercy. Not to mention running backs and offensive linemen. Playing with a raw violence that is rare even when judged by the bare-knuckle standards of his sport, Ernie Holmes knows how to slaughter an offense.

On most teams his performance, and personality, would make Holmes famous. Not on the Steelers. With Pittsburgh, he is not even the best-known defensive lineman. There are three reasons: Fellow Tackle "Mean" Joe Greene and Ends L.C. Greenwood and Dwight White, each a prototype of menace at his position and a striking figure off the field. Greenwood, 29 is a brutal tackler, although he says he hates contact and would rather not be known as a football player. Greene, 29, after a season of tossing linemen and runners around like rag dolls, goes home to cultivate his vegetable garden. As for White, 26, it is hard to know exactly what he will do at any time. "There's no question that I'm schizoid," he says. "I might be three or four people. I know I can be evil."

These are the men who make up the meanest front four in football, a half ton of trouble for any offense. Moving like a band of marauding behemoths (average size 6 ft. 4 in., 260 lbs.), they smother runners at the line of scrimmage, flatten passers, and send offensive linemen into disarray. "There are some great lines in the league," says Washington Redskins Head Coach George Allen, architect of one himself, "but the edge has to go to Pittsburgh. They put fear in the heart of a passer."

They do more than that. Dumping quarterbacks a league-leading 40 times last season was only the beginning of the front four's contribution to the Steelers. They set the tone for the entire defense and it was the defense that carried the 42-year-old Pittsburgh franchise to its first Super Bowl championship last year. The creation of patient, low-key Head Coach Chuck Noll, who drafted all but two of the starting defensive players, and Steelers Founder and Owner Art Rooney, who gave Noll the backing he needed to build slowly over the past six years, the defense is the cornerstone of Pittsburgh's leadership in the N.F.L. When Pittsburgh defeated Minnesota 16-6 in the Super Bowl, the defense limited the Vikings to 17 yds. rushing. Minnesota Running Back Chuck Foreman spoke for the league when he pleaded with the Steeler front four: "C'mon, you mothers, give us a yard."

Before this season ends, that call may well be heard again. Going into last weekend's game against the stumbling New York Jets the Steelers were riding an eight-game winning streak and an overall won-lost record of 9-1. That was good enough to pui them in first place in the Central Division of the American Conference the toughest division in the N.F.L. Their biggest conference obstacle on the way to the Super Bowl is a likely playoff showdown with the rugged Oakland Raiders. If the Steelers survive that, they will probably face either the Vikings or the Los Angeles Rams in the Super Bowl next month in Miami.

A Super Bowl in Florida will be the natural conclusion for a sunny NFL. season. Despite, or perhaps because of, the collapse of the rival World Football League, the N.F.L. this fall registering a jump in attendance (averaging 56,000 per game) and an increase in TV ratings. And why not? Some 40% of the games are being won by 7 points or less, not to mention a rash of sudden-death thrillers.

It is ironic that four of the key protagonists of this season should be Charles Edward ("Joe") Greene, Dwight Lynn White, Ernest Lee Holmes and L.C. Henderson Greenwood. Though front fours have been well publicized in pro football, the Rams "Fearsome Foursome" and the Vikings "Purple People Eaters during the past decade, quarterbacks and running backs still remain the celebrities of the sport. Certainly the action along the line of scrimmage gets only passing attention from TV cameras and fans. But this trench warfare is as fierce as anything in sport. Grunting and cursing, players club, ram and pound each other in two- and three-second rumbles that begin anew with every play.

Until about 15 years ago, the defensive lineman's primary objective was to come out of the rumble stopping the run. No longer. Faced with increasingly sophisticated passing attacks, the interior defensive line must now think first about rushing the passer. To do that, which requires them to overcome powerful, oversize blocking linemen who launch the offensive attack, front fours operate as a team with complicated strategies of their own.

In Pittsburgh, planning starts every Tuesday morning at the Steelers' offices in Three Rivers Stadium when Joe Greene and Co., including back-up lineman Steve Furness, gather with Defensive Line Coach George Perles to go over movies of the previous Sunday's game. Screening a specially edited reel that covers only defensive play by Pittsburgh, Perles, 41, a former Michigan State tackle, shows his players their mistakes in a numbing montage of slow motion, stop-action and reverse-run images. On Wednesday, films of the next opponent come under scrutiny. The group focuses on the abilities of each offensive lineman: Has some bull-like youngster been developing deceptive moves? Has a veteran fallen into a habit pattern that tips off his plans? Perles points out the formations and plays he thinks the opposition will use. In afternoon practice sessions, the front four polish the latest pass-rushing tactics Perles has devised.

Today a team wins or loses on games within the game. A particular "game" can be a certain pass-rushing pattern. Instead of sending each lineman driving straight ahead into blockers on the shortest route toward the quarterback, a game can use one lineman to run interference for another. The basic Steelers games are called "me" and "you" (you because of the U-shaped route one of the linemen runs, me just as the opposite of you). In the me game, Left End L.C. Greenwood will push himself and his blocker inside toward the offensive guard, who would normally block Left Tackle Joe Greene. While Greenwood is keeping that area clogged and trying to bust through himself, Greene is cutting to the open area outside and sweeping back in on the quarterback. The you game is the reverse, with Greene running interference on the outside while Greenwood cuts over the offensive-guard position (see diagram).

Right End Dwight White and Right Tackle Ernie Holmes use the same tricks on their side of the line, often on the same play as Greenwood and Greene. These combinations are called "double" games. To put the offensive line further off balance, Greenwood and Greene will sometimes charge using a me while White and Holmes employ the you. In still another refinement, the two tackles can run their own separate game, crossing paths as they bull ahead. That is called a "torn" game (T for tackle and torn).

Last week, in the Pittsburgh-Houston game, the payoff for all this strategy was obvious. In the second period, with the Steelers ahead only 9-3 and the Oilers beginning to show some offensive muscle, Greenwood wheeled in over the middle of the offensive line, forcing Houston Quarterback Dan Pastorini out of the pocket. As he fled, Pastorini threw a wild pass that was intercepted, setting up what proved to be Pittsburgh's game-winning touchdown. (Final score: Steelers 32-9.) The turnover was the result of a me game George Perles had devised for certain third-down passing situations.

The front four, of course, do not neglect defense against running plays, and for these too they employ more than one tactic. Rather than lining up in the traditional formation, defensive ends opposite offensive tackles, defensive tackles against guards, and the middle linebacker responsible for the center, the Steelers use what is called a "stunt 4-3." In this alignment, Joe Greene edges toward the center. His assignment: to stop both guard and center, leaving the middle linebacker unmolested, free to deck the runner as he crosses the line of scrimmage.

The best devised strategies, of course, are only as good as the players executing them, and that is where Pittsburgh has the advantage over any other team in the league. "What impresses me," says George Allen, "is that they're all so quick. They move like linebackers." Alex Karras, Monday football broadcaster and former all-pro defensive tackle with the Detroit Lions, puts it this way: "It's simple. They're the biggest, strongest, fastest and meanest." The players speak for themselves:

White: "That offensive lineman is there to stop me from getting to the quarterback. He might as well forget it. He'll just get caught between the stink and the sweat. I'll kick, slap, gouge. On that field, I take no prisoners."

Greene: "I hate to lose. It makes me ugly. You don't want to know me after we lose a game."

Greenwood: "If I have to intimidate, I can pound on a man's head the whole game."

Holmes: "I don't mind knocking somebody out. If I hear a moan and a groan coming from a player I've hit, the adrenaline flows within me. I get more energy and play harder."

For such huge men, the front four have exceptional speed. With hands the size of bear paws and thighs the thickness of a railroad tie, Joe Greene measures 6 ft. 4 in. and weighs 275 lbs. Even so, he drives through the 40-yd. dash in less than five seconds, as fast as many running backs. Dwight White (6 ft. 4 in., 255 lbs.) and Greenwood (6 ft. 6 in., 230 lbs.) are faster, and Holmes (6 ft. 3 in., 260 lbs.) is only a minisecond slower.

These reserves of strength and speed are harnessed in physical techniques used to bull past blockers. All four start with the head butt, driving their helmets into the heads of the opposite offensive linemen like bull moose battling for their lives. Once the offensive lineman has been hit, each man has a specialty. Greenwood likes to use the "slip" move, pushing past his blocker. White prefers to knock his opponent aside with an "uppercut" shove under the shoulder. Holmes is a master of the "club," using one of his blacksmith forearms to belt a blocker to the side, and the "push and pull," in which he pushes a guard off balance and then pulls him aside. Greene is an expert at all four techniques. "When Joe stomps you, it's not infuriating," says Steeler Center Ray Mansfield, who faces him in practice. "It's more like frightening. Did you ever see a dog get hold of a snake?"

The front four are so aggressive, in fact, that it sometimes works to their disadvantage. Offensive plays that capitalize on a hard defensive rush have gained yardage against the Steelers this year. Screen passes, for example, are designed to lure pass rushers toward the quarterback, who then dumps the ball to a runner waiting a few yards downfield.

Of the front four, Ernie Holmes is the most volatile, living and playing precariously close to the edge of rage. "I don't know what my life is," he says, "except there is something pounding in back of my head."

Nearly three years ago, his marriage broke up, depriving Holmes of two adored sons. Driving through eastern Ohio after leaving them, he started firing a pistol at trucks. Before he was stopped, Holmes shot at a police helicopter and wounded a cop during a chase through woods. "Three trucks tried to drive me off the road," he says. "It was all I needed to snap."

He pleaded guilty to assault with a deadly weapon. After the Steelers promised to provide help for him, he was placed on five years' probation. Holmes spent two months in a psychiatric hospital. "I was considered stone crazy until the Super Bowl last year," he says. "Now I'm back on the bases."

Last season, in what he describes as a "mystic haze," Holmes shaved his head, leaving only an arrow-shaped pattern of hair facing forward, hence the nickname "Arrowhead Holmes." These days, for relaxation, Holmes tends a collection of exotic fish, including a piranha that feeds on a goldfish a day. "It's the destructive time of year," Holmes notes. He himself will consume a light meal of 15 spareribs and nine chicken parts, his lifelong nickname is "Fats", and occasionally polish off heroic amounts of Courvoisier cognac in an evening. His hard times appear to be over. Earning a comfortable living like his three colleagues (exactly how much, they won't say), Holmes finds tranquillity in shooting pool, or playing chess on a board that reflects his expansive nature: it is three feet square.

He was born in Jamestown, Texas. Indeed, all of the front four, except White, whose father was college-educated, come from poor rural backgrounds in the South. They all played their college football for obscure schools. For Holmes, it was Texas Southern University in Houston, where campus buildings "had bullet holes the size of silver dollars" from student riots.

The product of a far more peaceful campus, East Texas State, Dwight White, with his missing front tooth and boyish grin, makes a deceptively mild first impression. He laughs easily in a high-pitched voice and is the teaser and clown of the front four, letting out jungle cries in practice, needling Joe Greene about the publicity he gets, and booming to reporters, "I am the epitome of masculinity." But just beneath the engaging extravert there is a hair-trigger temper and barely repressed violence. "There are circumstances," he says, "when I can get so angry and pissed-off that I'll do damage if I don't cool down fast."

White, a bachelor, now rents an apartment in the fashionable Squirrel Hill section of Pittsburgh, after rooming briefly with Joe Greene. The separation reflects the general state of the relationship between the four defenders: cordial but not intimate. "I couldn't live with Joe," White explains. "He'd put on music late at night."

Dwight does play chess with Greene and also Holmes. He is the most active of the four in the world beyond the Steelers. In the offseason, he works for a Commerce Department program that finds jobs for black college students from Pittsburgh's Hill district.

If White is usually the liveliest of the front four, L.C. Greenwood can be the quietest. "Most of the time I like to be by myself," he says. "I'm a loner. I want to lay back and live." That philosophy is reflected in almost everything unmarried L.C does, from collecting American Indian jewelry and playing cards to shunning contact during practice. "1 try to preserve myself for the game," he says. "That's when I come to play."

Of the four, Greenwood struggles hardest to escape his image as a jock. "I can do without the inhuman looks people give me," he says. "Even kids do it. When I tried to do some teaching in the offseason, the kids said, 'Hey, man, you're a football player, not a teacher. We don't want you here.' I'm just an object."

Greenwood began taking football seriously as a high-school freshman in Canton, Miss. Hoping to get a degree in pharmacy at college, Greenwood attended Arkansas A M & N on a football scholarship. By the time he was graduated in 1969, L.C. had abandoned his hopes of owning a drugstore; he reported to the Steelers' training camp as their tenth-round choice. "I couldn't believe it when I made the team," he says.

That same year, another lineman made the cut: Joe Greene. Arriving overweight after a contract holdout, the Steelers' first-round draft choice looked like a pushover to some Steeler veterans. As soon as he started blowing by blockers, they knew better. They also learned that off the field Joe is a sensitive, gentle friend, still trying to overcome natural timidity and live down the image that he is a bully. (He got his nickname, which he does not like, while playing football at North Texas State University, where the team was called the "Mean Greens.") "I come off as being ugly," he complains. "Sometimes I get the feeling I am that way. I don't like what all that makes me become."

So far his image has not made much of a dent on his character. At home in Duncanville, Texas, in the offseason, Greene lives in a sprawling ranch house. He enjoys just sitting around watching his three children, Charles, 7, Edward, 6, and Joquel, 2. "I've missed a lot of their growing up," he says. Other times, Greene is happy weeding the cucumbers and squash in his garden, sipping a glass of white wine while he listens to the Temptations, or helping his wife Agnes clean house. A compulsive tidier, Joe says, "It gives me peace of mind to know things are in their place."

One thing that does not give Greene peace of mind is the predominantly white cast of his neighborhood. "I'm not a pacesetter," he says. "If I'd known earlier how this neighborhood was composed, I probably would have chosen somewhere else." Dwight White felt the same way recently when he bought a home outside Dallas. Such unease among black athletes is nonexistent on the field. For one reason, blacks equal or outnumber whites on some teams and account for about a third of the N.F.L.'s 1,100 players. For another, equality of position is accepted, quarterback, the last major barrier, has fallen with the Los Angeles Rams black starter James Harris. "It's a competitive game," says White, "and color isn't a factor."

It certainly hasn't stopped Joe Greene from becoming the Steelers' leader. "Joe's first year," says Steeler Linebacker Andy Russell, "I didn't see how all the emotionalism could be real. He's the only guy I know, he can be playing a great game himself, but if the team's losing he gets into a terrible depression." Art Rooney senses the same fire. "That Joe Greene," he says. "I've never seen a player lift a team like he does."

When Joe lifts, there is more than enough talent to respond. Behind the front four on defense are three of the most mobile linebackers in the league: eleven-year Veteran Russell on the right side, lanky Jack Lambert in the middle, and hard-hitting Jack Ham on the left. Behind them are four defensive backs with the speed and experience to spoil most passing patterns.

On the offense, Quarterback Terry Bradshaw, 27, has been slow developing, but since late last season he has directed the Steeler attack like a young Johnny Unitas. This year he has completed better than 60% of his passes, scrambled for first downs, and given his powerful backfield plenty of opportunities to carry the ball. When Franco Harris is at fullback, that may be all a team needs to win. The son of an Italian mother and a black father, Harris is a runner of the Jim Brown model: strong, shifty and astonishingly difficult to bring down. Last year he was the Most Valuable Player in the Super Bowl, breaking the rushing record for the game as he rumbled for 158 yds. This season Harris trails only O.J. Simpson in rushing stats.

Bradshaw has other weapons as well. Second-year Wide Receiver Lynn Swann has become one of the best pass catchers in the N.F.L., moving through his patterns with the speed of a college sprinter and the fakes of a ten-year veteran. Running Back Rocky Bleier, who was wounded by shrapnel while serving with the Army in Viet Nam, last year became a bruising blocking back for Harris, as well as a dangerous runner in his own right. Helping it all come together in offense is an experienced, hard-charging line that can move out almost any front four, except their own.

If the offense falters, the Steelers can always turn to the front four to hold off the opposition for a while, and perhaps even to score. Joe Greene dreams about just that possibility. "I visualize techniques," he says. "Some of them are just ungodly. Run over a guy, hurdle, jump six feet, put three or four moves on him so he freezes. No flaws. Perfect push and pull on the guard, jump over the center. Another blocker, slap him aside. Block the ball when the quarterback throws it, catch it, and run 99 yards." If that's the defense,

Pittsburgh shouldn't have to wait another 42 years to win a second championship.